Introduction

In the previous post, we explored how Block’s Compute Security team uses our custom OPA-based admission controller, Kube-policies, to enforce strict security guardrails for applications deployed in our Kubernetes platforms. But, workload configurations are only half of the battle. Even with perfect workload security configurations, your software supply chain remains vulnerable: an application can still run an unexpected image, a compromised artifact, or a tag that now points to something different than what was reviewed.

This second post focuses on software supply chain controls, specifically binary authorization (BinauthZ), our guardrail that answers, "Should this container image be allowed to run here?" We'll discuss the risks this solves and how we integrated artifact verification directly into our admission controller.

Problem Statement

Kubernetes doesn't natively enforce artifact integrity and provenance at admission time. While container runtimes can restrict which registries are allowed, this doesn't verify how an image was built or who signed it. Given an image URI, Kubernetes will pull and run it regardless of whether that image came from your CI, was reviewed by your organization, or was swapped after the fact. This creates a supply chain security gap. Clusters can be secure with workload configuration while still executing untrusted code.

We needed a guardrail to ensure any code entering the cluster satisfies strong artifact security and provenance standards.

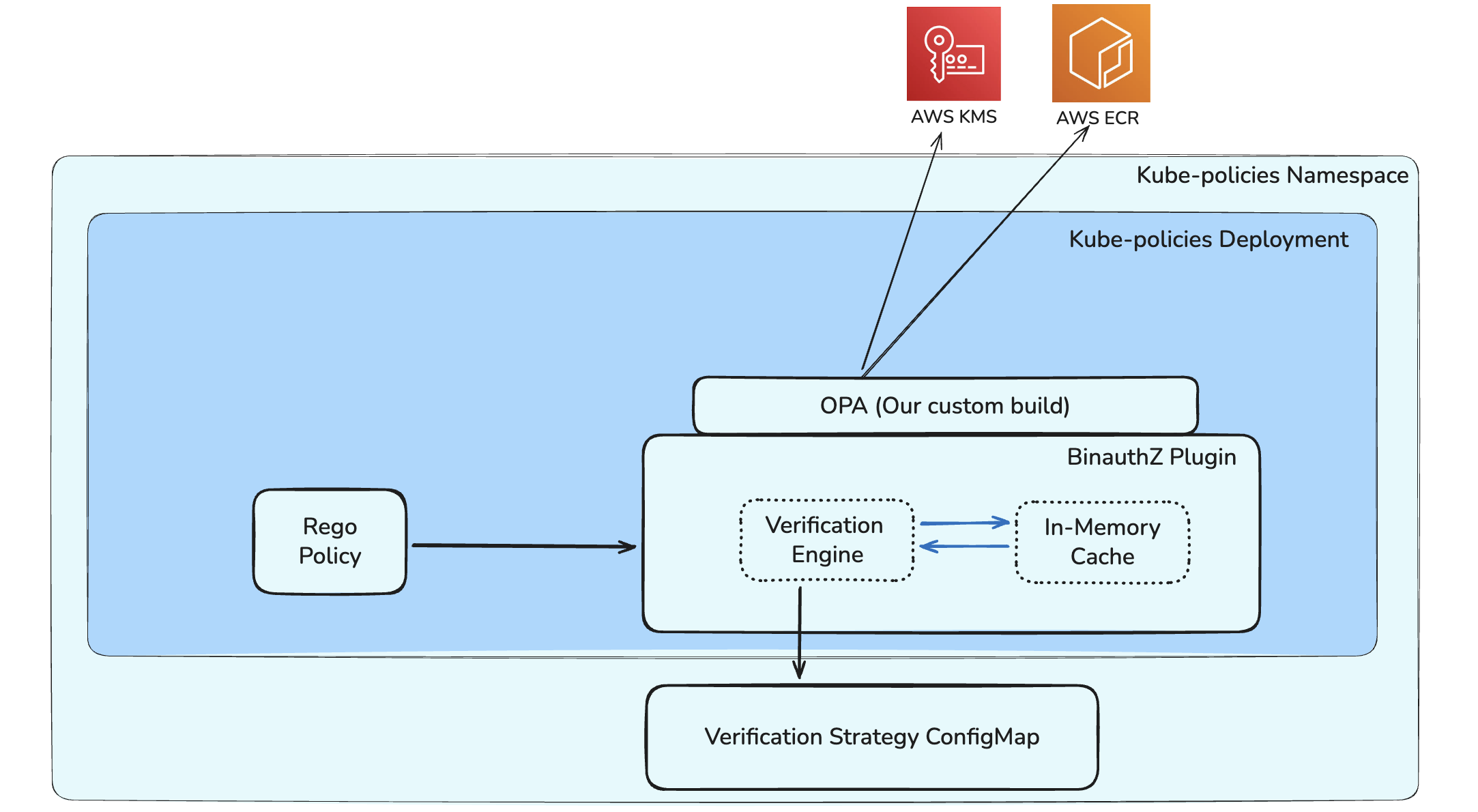

Enter our decision to extend our OPA based admission control service, Kube Policies. We developed the BinauthZ plugin that cryptographically verifies container image signatures and attestations at admission time. BinauthZ checks that images are signed by trusted keys and carry attestations that describe how they were built.

BinauthZ’s Supply Chain Framework - SLSA

SLSA (pronounced "salsa," short for Supply Chain Levels for Software Artifacts) is a framework for hardening the software supply chain. It focuses on questions like: Where did this artifact come from? Was it built by a trusted system? Can we verify it hasn’t been tampered with? Do we have auditable provenance guarantees? SLSA defines maturity levels and a set of controls around build integrity and provenance.

In simple terms, SLSA tells you what “good” looks like for supply chain security, and BinauthZ is the control that enforces those properties.

As a publicly traded technology company providing financial services, Block builds security capabilities that satisfy the rigorous standards outlined in Sarbanes-Oxley and PCI DSS. BinauthZ enables continuous enforcement of artifact integrity and provenance without slowing delivery. By enforcing artifact integrity and provenance at admission time, it ensures continuous enforcement of change-management and clear audibility without slowing delivery.

Technical Challenges

Resource Types

Container images can appear in Pods directly, but they’re also nested inside controllers (Deployments, Jobs, CronJobs, etc.), and each type structures its pod template differently. Add ephemeral containers, CRDs, and Helm-rendered complexity, and it’s easy to end up with brittle “if kind == X then dig here” parsing that constantly lags Kubernetes reality.

Scale

Signature verification requires network calls to ECR to fetch signature artifacts and (in our case) to AWS KMS to validate them. In Kubernetes, a single Deployment can fan out into many Pods in seconds.

A small change can translate into a burst of verification traffic. Without careful design, that burst can turn into an availability risk: slower admissions on the API-server critical path and increased chances of hitting ECR/KMS rate limits in large clusters.

Verification Beyond “is it signed?”

A signature confirms one important thing: a trusted key signed this artifact. For higher-order guarantees such as “this image was produced by an approved CI pipeline” or “it was built from a convergence/dual‑approved branch” we need to also validate attestations (provenance metadata).

Requirements

With those challenges in mind, we defined a set of requirements for BinauthZ.

-

Provenance Assurance

We must be able to prove that an image running in our clusters was produced by a trusted CI system. That means cryptographic signature verification plus the ability to validate build metadata (attestations) when policy needs stronger provenance signals.

-

Multi-platform

Our platforms don’t all look the same. BinauthZ must work across Kubernetes environments with different registries, repositories, and trust keys, and onboarding a new platform should be configuration-driven, not a code change.

-

Performance at scale

Verification has to be fast enough for real-time admission. The system must avoid becoming a bottleneck on the API-server critical path and should not materially impact Pod startup times, even during large rollouts.

-

Observability

We need clear visibility into both security outcomes and operational health. For example:

- “Are we blocking deploys? Why?”

- “Are we efficiently caching results, or repeating expensive verification calls?”

- “Are failures real policy violations or transient dependency issues?”

-

Minimal User Disruption

When developers follow paved paths (signed images from approved sources), verification should be invisible. We shouldn’t require new manifest changes beyond choosing the correct, approved image references, and failures should be actionable when they occur.

Why an OPA Plugin?

For a critical project that enforces binary integrity and provenance at admission time, we had two main choices. Either adopt a third-party vendor solution, or extend our existing admission controller, our OPA-based admission controller, that we are running in production at scale.

We ultimately chose OPA for long-term advantages:

-

One admission controller, not two

We already run kube-policies in production, which is an OPA-based admission controller that enforces our workload guardrails. Introducing a second admission controller in the critical path would have meant another control plane component, new deployment mechanics, new failure modes, and more operational surface area. Because admission controllers can become a single point of failure for the entire cluster, we prioritized reusing the controller we already operate and trust. Building BinauthZ as an OPA plugin let us extend that existing system, reducing reliability risk and avoiding the operational overhead of running two parallel admission stacks.

-

Reduced vendor risk, with meaningful $$ savings

A vendor solution would have locked us into a per-node pricing model, driving recurring spend up as our clusters scale and creating ongoing exposure to price increases outside our control. Equally important, building on OPA gave us the freedom to experiment quickly and shape the solution around our internal workflows rather than adopting a vendor’s one-size-fits-all model. By building on OPA’s open-source platform, we avoided that long-term cost curve and reduced procurement friction.

Once we committed to OPA as the platform, we still had a design choice inside OPA. Either implement BinauthZ as “just a built-in function,” or as a real plugin with a Rego-callable interface. We landed on a hybrid design: a custom built-in function for core verification logic, plus a lightweight plugin to integrate with OPA’s metrics registerer and logging. This model would give us the following benefits:

- Lifecycle + platform integrations: The plugin model lets us hook into OPA’s lifecycle (startup/readiness) and connect to OPA’s centralized logging and Prometheus registerer.

- Stateful performance at scale: Verification requires external calls (ECR + KMS). The plugin owns the cache implementation for verifier instances and verification results.

Plugin Components

The BinauthZ plugin is a set of components that work together to make “verify this image” fast, observable, and policy-friendly. BinauthZ has the following components:

- The

verify()Policy Facing API - Verification Engine

- In-memory Caching

- Configurations

The verify() policy-facing API

At the policy layer (Rego), calling BinauthZ is intentionally simple. Policy extracts the set of container image references from the incoming Pod spec and makes a single call like verify([image1, image2, ...]). Rego policy focuses on what to require (signed, provenance-attested, exceptions), while the plugin handles the how (parsing, strategy selection, verification, caching, and errors).

Within the Plugin, Policy calls go through a single entry point that takes a list of strings containing URIs of container images. It uses OPA’s built-in context (useful for cancellation) and returns a response that Rego can parse and validate.

go1// VerifyImages is the verification entrypoint 2func (p *BinauthZPlugin) VerifyImages(bctx rego.BuiltinContext, opaInput *ast.Term) (*ast.Term, error) { 3 // ... 4 eg, ctx := errgroup.WithContext(bctx.Context) 5 // ... 6} 7 8// VerifyResult represents the result of verifying an image 9type VerifyResult struct { 10 Verified bool `json:"verified"` 11 Attestations []map[string]any `json:"attestations,omitempty"` 12 Image string `json:"image"` 13 Error string `json:"error"` 14}

BinauthZ Plugin Verification Engine

The verification engine has three main tasks for each image:

- Parse the image reference

- Select a verification strategy via the factory

- Verify signatures and extract attestations

It also runs verification for all images concurrently using errgroup, and respects request cancellation via the builtin context.

go1imageRef, parseErr := name.ParseReference(image) 2// ... 3strategy, strategyErr := p.factory.GetVerificationStrategy(ctx, imageRef) 4// ... 5attestations, verifyErr := strategy.VerifySignatures(ctx, imageRef)

Caching

When Kubernetes admits a workload, BinauthZ verifies every container image is signed by the right key. In practice, at production scale, “verify every container, every time” turns into a high-QPS distributed system that leans heavily on AWS ECR (to fetch signatures) and AWS KMS (to verify them). Without caching, the verification path becomes both expensive and fragile enough to throttle itself into an outage.

The simple implementation repeats identical work constantly because the same popular image digest might appear in:

- Hundreds of pods across namespaces

- Every node’s DaemonSet

- Multiple deployments during a rollout

- Retries when a webhook times out

Verifying each container image from scratch, every time, means repeatedly hammering the exact same ECR/KMS calls. To make this viable at scale, we implemented caching inside the BinauthZ plugin as a first-class component. (More details in the performance section)

Configuration

BinauthZ is configuration-driven, so onboarding a new platform typically doesn’t require code changes. The plugin loads a set of verification rules (image pattern → strategy → key URI) from configuration (packaged into OPA config via ConfigMap/env), and uses those rules to map each image reference to the correct verification strategy and trust key. This keeps enforcement consistent while allowing flexibility across registries, repository layouts, and signing keys.

go1// in the configmap 2verificationRules: 3 # Default signature verification 4 - imageGlob: "123456789012.dkr.ecr.us-west-2.amazonaws.com/**" 5 strategy: "signed" 6 keyURI: "aws-kms://arn:aws:kms:us-west-2:123456789012:key/aaaaaaaa-bbbb-cccc-dddd-eeeeeeeeeeee" 7 - imageGlob: "localhost:5000/**" 8 strategy: "dev" 9 keyURI: "aws-kms://arn:aws:kms:us-east-1:000000000000:key/local-test-key" 10 11// Within the Plugin 12type Config struct { 13 // Embed the parsed configurations 14 Cache CacheConfig // Cache config is loaded directly by conf 15 Verification VerificationConfig `conf:"-"` // Mark as ignored by conf parser 16 17 // Store the raw YAML string temporarily for loading 18 VerificationConfigYAML string `conf:"VERIFICATION_CONFIG_YAML"` 19} 20 21type VerificationRule struct { 22 ImageGlobPattern string `yaml:"imageGlob,omitempty"` 23 Strategy string `yaml:"strategy"` 24 KeyURI string `yaml:"keyURI"` 25 26 imageGlob glob.Glob // compiled from imageGlobPattern and used for matching 27}

Strategy-Based Implementation

Rather than a single hard-coded verification path, the plugin uses a strategy abstraction. The goal of the strategy based implementation is that given an image reference, we use image/configuration specific requirements for different environments. A factory selects a strategy based on the configured rules (image pattern → strategy/key), then the selected strategy performs signature retrieval, verification, and attestation extraction. This keeps the system extensible.

The key point is that Rego policy will always call the same verify() API but the plugin will route the image verification behavior using configuration. Rego doesn’t need to know how verification works.

go1type Strategy interface { 2 VerifySignatures(ctx context.Context, imageRef name.Reference) ([]map[string]any, error) 3} 4 5type VerificationFactory interface { 6 GetVerificationStrategy(ctx context.Context, imageRef name.Reference) (Strategy, error) 7 SetLogger(logger logging.Logger) 8} 9 10type Verifier interface { 11 VerifySignature(sig oci.Signature) (attestation map[string]any, err error) 12} 13 14if rule.imageGlob.Match(imageRef.Name()) { 15 verifier, err := f.cache.getOrCreateVerifier(ctx, rule.KeyURI, func(ctx context.Context) (verification.Verifier, error) { 16 return verifier.NewSigstoreKMSVerifier(ctx, rule.KeyURI) 17 }) 18 // ... 19 switch rule.Strategy { 20 case "awesome-ci": 21 return verification.NewAwesomeStrategy(ctx, f.awsECRClient, verifier) 22 case "other-ci": 23 return verification.NewDefaultStrategy(ctx, f.awsECRClient, verifier) 24 // ... 25 }

Signature Verification and Attestation Extraction

We verify signatures using the Sigstore/cosign ecosystem, with AWS KMS as the trust anchor. In practice, BinauthZ constructs a verifier from a KMS key URI (a reference to the public key material managed by KMS) and relies on an AWS IAM role for authorization. The core logic is straightforward. If verification succeeds, we’ve proven that a key we trust produced a valid signature over the image’s cosign payload, which means the image matches an approved signing boundary.

Cosign signatures also carry a signed JSON payload. After verifying the signature, BinauthZ extracts relevant metadata from that payload and returns it as attestation data alongside the verification decision, so Rego can apply rules.

Here’s an example result returned to Rego after a successful verification:

json1[ 2 { 3 "image": "123456789012.dkr.ecr.us-west-2.amazonaws.com/deployable/payments@sha256:abcd...", 4 "verified": true, 5 "attestations": [ 6 { 7 ... 8 "repo": "block/payments-service", 9 "build_id": "7421931", 10 "commit_sha": "9c1e2f0c2d7e4a6b...", 11 "build_timestamp": "2025-12-17T02:41:09Z" 12 "BRANCH": "main", 13 "IS_DEFAULT_BRANCH": "true", 14 "build.system": "blockkite", 15 } 16 ], 17 "error": "" 18 } 19]

Pod as the Boundary

We deliberately standardized enforcement at the Pod boundary. Pods are the unit that actually executes, and controllers ultimately create Pods. We focus on verifying the images that appear in the Pod spec that would run. This keeps the developer experience consistent (“the thing that runs is what gets verified”) and avoids a long tail of per-kind parsing logic that’s hard to maintain.

Performance at Scale

We wanted to treat latency as a first class requirement of kube-policies BinauthZ. Our webhook is configured with a hard timeout of 10 seconds (failurePolicy: Fail, timeoutSeconds: 10). That’s our total budget to verify all images in a request, no matter how many containers are involved. To meet that constraint, we leaned on two design choices: concurrency and caching.

A single workload spec can reference multiple images. Instead of verifying each image serially, which scales linearly, we verify each image in its own go-routine using errgroup.WithContext. All go-routines share the same context from OPA’s builtin call so the entire batch is bounded by the admission deadline.

go1ch := make(chan VerifyResult, len(images)) 2eg, ctx := errgroup.WithContext(bctx.Context) 3 4for _, image := range images { 5 image := image // Capture range variable 6 eg.Go(func() error { 7 result := p.verifyImage(ctx, image) 8 select { 9 case ch <- result: 10 return nil 11 case <-ctx.Done(): 12 // If context is canceled, returning an error 13 // will cause eg.Wait() to return this error. 14 return ctx.Err() 15 } 16 }) 17} 18 19// Wait for all goroutines to complete. eg.Wait() returns the first 20// non-nil error returned by an eg.Go func, or nil if all succeed. 21// In this specific case, it will likely only return non-nil if ctx.Done(). 22err := eg.Wait() 23 24// It's now guaranteed that all sends to 'ch' have completed. 25close(ch)

In practice, this design has been very useful to use because rollouts cause bursts and the latency trends towards slowest single image. Also, most admission traffic during rollouts is repetitive. We added two ARC caches with TTLs:

- Verifier cache: stores verifier instances (e.g., KMS-backed verifier keyed by keyURI) so we don’t rebuild verifiers repeatedly.

- Result cache: stores the final verification result for an image string, so we can short-circuit the entire remote verification path.

go1type pluginCache struct { 2 // This cache stores verifier instances, keyed by a unique identifier (e.g., KMS ARN, key ID). 3 verifiers gcache.Cache 4 // We also cache verification *results* to allow short-circuiting the entire process. 5 results gcache.Cache 6} 7 8verifiers := gcache.New(config.VerifiersCacheMaxSize).ARC().Build() 9results := gcache.New(config.ResultsCacheMaxSize).ARC().Build() 10 11func getOrCreateGeneric[K comparable, V any]( 12 // ... 13) (V, error) { 14 // ... 15 if createErr != nil { 16 // If it's a transient error, skip caching but still return the value + error 17 if errors.Is(createErr, errdefs.ErrTransient) { 18 return newValue, createErr 19 } 20 // ... 21 } 22 // Cache the newly created value 23 _ = cacheInstance.SetWithExpire(key, newValue, ttl) 24 // ... 25}

Failure Modes & Error Handling

At scale, dependencies fail from time to time. ECR can throttle, KMS can blip, network can flap. We explicitly classify certain failures as transient and skip caching them so a brief dependency issues doesn’t poison the cache for an hour. We shouldn’t treat a network blip the same as an invalid signature. Result of a misconfigured image reference shouldn’t stay in cache for an hour (Our cache TTL).

Common failure modes:

Understanding how BinauthZ fails is as important as understanding how it works. Here are the failure modes we designed for:

| Failure Mode | Cause | System Response |

|---|---|---|

| Invalid image reference | Malformed URI, invalid digest format | Permanent error, cached, policy denial |

| No matching rule | Image from registry not in configuration | Permanent error, cached, policy denial |

| Unsigned image | Image exists but has no signature artifact | Permanent error, cached, policy denial |

| Invalid signature | Signature doesn't match trusted key | Permanent error, cached, policy denial |

| Registry throttling | ECR rate limits exceeded | Transient error, not cached, retry allowed |

| KMS unavailable | Service outage or network partition | Transient error, not cached, retry allowed |

| Network timeout | Connectivity issues to ECR or KMS | Transient error, not cached, retry allowed |

| Webhook timeout | Verification exceeds admission deadline | Context cancelled, partial results possible |

The first four represent genuine policy violations or configuration issues. The next three are infrastructure hiccups that typically resolve themselves on retries. The last one is a boundary condition where our 10-second admission deadline is exceeded.

Sentinel errors: BinauthZ defines a set of sentinel errors that categorize failures across the verification pipeline. Each error represents a distinct failure mode to help us identify where things went wrong and how to respond.

go1var ( 2 ErrParsingImageReference = errors.New("image reference could not be parsed") 3 ErrInvalidRegistry = errors.New("image is not from an approved registry") 4 ErrGetStrategy = errors.New("getting verification strategy") 5 ErrUnsupportedVerificationStrategy = errors.New("unsupported verification strategy") 6 ErrGetSignatures = errors.New("getting image signatures") 7 ErrSignatureVerification = errors.New("image signature verification") 8 ErrTransient = errors.New("transient error") 9 )

Distinction between transient and permanent failures are also very important for error handling, but especially important for caching behavior. For example, a network timeout might succeed on the next attempt.

Permanent errors indicate a failure that isn’t going to change in the next attempt:

- Invalid image reference (malformed URI or digest)

- No matching verification rule (image from unapproved registry)

- Cryptographic signature verification failed

- Image unsigned or missing from approved namespace

Transient errors indicate a temporary failure:

- Network timeouts

- Registry throttling (ECR rate limits)

- KMS service unavailability

go1func IsErrorTransient(err error) bool { 2 if err == nil { 3 return false 4 } 5 6 // Definitive cryptographic failures are permanent 7 var invalidSig *types.KMSInvalidSignatureException 8 if errors.As(err, &invalidSig) { 9 return false 10 } 11 12 // Check for known permanent error patterns 13 errorString := err.Error() 14 if strings.Contains(errorString, "invalid signature when validating ASN.1 encoded signature") { 15 return false 16 } 17 if strings.Contains(errorString, "crypto/rsa: verification error") { 18 return false 19 } 20 21 // Default to transient - assume retriable unless proven otherwise 22 return true 23 }

The transient/permanent distinction directly affects caching behavior. Permanent errors are cached. There's no point verifying an image that will always fail. Transient errors skip the cache entirely to allow for retries.

go1if createErr != nil { 2 // Transient errors skip caching - allow retry on next request 3 if errors.Is(createErr, errdefs.ErrTransient) { 4 return newValue, createErr 5 } 6 // Permanent errors get cached to avoid repeated failing calls 7 _ = cacheInstance.SetWithExpire(key, newValue, ttl) 8 }

Verification errors are surfaced to Rego so that policies can then decide how to handle different failure modes.

go1type VerifyResult struct { 2 Verified bool `json:"verified"` 3 Image string `json:"image"` 4 Attestations []map[string]any `json:"attestations,omitempty"` 5 Error string `json:"error"` 6 }

The Error field contains the human-readable error chain, while Verified: false signals the policy to apply denial rules. This separation lets policy authors write simple rules ("if not verified, deny") while still having access to detailed error information for logging and debugging.

Policy (Rego) Integration

BinauthZ is integrated into kube-policies as a custom OPA builtin named verify(). At runtime, our OPA distribution registers verify and wires it to the Go implementation. Rego decides what to enforce, and where, while the builtin handles the hard part of talking to registries/KMS and verifying signatures/attestations.

go1rego.RegisterBuiltin1( 2 ®o.Function{ 3 Name: "verify", 4 // Note that we're using type `types.A` here for both argument and return types. 5 // We accept a list of container images (requires type Any) 6 // and we will return whether the verification was successful or not. 7 Decl: types.NewFunction(types.Args(types.A), types.A), 8 9 // OPA docs recommend setting these for all functions that perform IO. 10 // Memoize: true tells OPA to cache results within a single evaluation, 11 // so if multiple rules call verify() with the same input 12 // during one admission decision, the call only happens once. 13 Memoize: true, 14 Nondeterministic: true, 15 }, 16 BinauthZPlugin.VerifyImages, 17)

Example verification:

Platforms integrate BinauthZ by adding a small wrapper policy that:

- Extracts container images from the admission request.

- Calls verify(images_to_verify).

- Applies platform-specific rules.

- Emits a single, consistent deny message format.

Here’s a baseline example:

go1deny_unverified_image contains reason if { 2 utils.is_request_valid 3 4 # Extract exceptions for a request beforehand. 5 # We don't want to calculate exceptions for each function call. 6 exceptions := BinauthZ.add_exceptions 7 8 # Collect the images in the request that do not have exceptions and 9 # are not from an allowlisted repository. 10 images_to_verify := BinauthZ.images_from_request(exceptions) 11 12 # If there are no images to verify, then we can skip the verification step. 13 not count(images_to_verify) == 0 14 15 # Send request to the BinauthZ extension to verify the images. 16 verify_results := verify(images_to_verify) 17 18 # Check each verification result for policy violations 19 some result in verify_results 20 21 # Check for any images that violate BASELINE policy and generate a message describing the problem. 22 some policy_violation in violates_baseline_policy(result) 23 reason := BinauthZ.error_message( 24 result.image, 25 policy_violation, 26 exceptions, 27 ) 28}

Observability and Metrics

We approached observability as part of the product. Kube-policies BinauthZ is in the critical path to deployments. That means during incident response times, or when something goes wrong, we need to quickly answer:

- What did we allow/block, and why?

- Are we reliable under rollout load?

Structured, component-based logging

BinauthZ emits structured JSON logs and consistently tags them with a component field. Operators can filter quickly and correlate event across the verification pipeline. At runtime we also inherit OPA’s centralized logging instance, so BinauthZ logs show up alongside the rest of the OPA logs, with the same formatting and sink configuration.

Prometheus metrics for cache effectiveness

A major performance lever for admission-time verification is avoiding repeated remote work during rollouts. To make that measurable, BinauthZ exports Prometheus counters (via OPA’s Prometheus registerer) for cache hits and misses.

These metrics let us quantify whether we’re efficiently short-circuiting repeated verification, and they’re a leading indicator for downstream dependency pressure (ECR/KMS traffic). For example, a sudden rise in result cache misses during a rollout typically predicts higher registry/KMS load and higher admission latency.

Operationally, kube-policies is covered by Datadog monitors that alert on admission controller health and user impact. The runbook documents alerts for:

- Validating Admission Controller Rejections: alerts when rejection rate exceeds a threshold.

- Fail Open: alerts when the admission controller is erroring/timing out enough to fail open (system namespaces).

- HTTP Request Duration: alerts when average response time rises (latency/SLO risk).

- Resource + k8s health: CPU, memory, replicas unavailable, pods failed/oomkilled, etc.

End to End (E2E) Testing

Testing an admission controller that verifies container signatures is fundamentally different from testing one that validates workload configuration. Our standard E2E tests deploy a resource and check whether it's admitted or denied. BinauthZ E2E tests require us to first build a fully functional signing pipeline, including cryptographic keys, container registries, and signature tooling, both in local systems and in CI, before we can even begin validating policy behavior. We could have used pre-signed artifacts for e2e suites, but that would only test verification and skip over real OCI interaction. By signing dynamically against local registries, we validate that BinauthZ correctly discovers and fetches signature artifacts through the same registry APIs it uses in production.

Test Cases within E2E

Our e2e suite validates that BinauthZ correctly enforces trust boundaries across the scenarios we encounter in production:

- Multiple CI systems: Different build pipelines sign images with different keys. We verify that an image signed by one CI system is rejected when deployed to a registry expecting a different signer.

- Cross-region key verification: Production uses AWS KMS multi-region keys (MRKs) for disaster recovery. We test that verification succeeds when using a replica key in a different region than the primary.

- Attestation validation: We verify that policy correctly evaluates attestation metadata. An image signed by a trusted key but carrying incorrect build system annotations should still be denied.

- Unsigned image rejection: Images without signatures must be blocked, even if they originate from an otherwise trusted registry.

- Metrics collection: We confirm that the BinauthZ plugin correctly exposes verification metrics to Prometheus.

For E2E tests, we need to reproduce how BinauthZ interacts with external services: container registries to fetch signature artifacts and AWS KMS to validate them. We couldn't simply mock the verify() API because that would test policy logic but not the actual verification engine.

Our E2E framework leverages go Concurrency primitives to bootstrap the following components before any test runs locally and in CI:

- LocalStack: Simulates AWS KMS for key management. We create asymmetric RSA-2048 signing keys and multi-region replicas to test cross-region MRK verification.

- Container registries: Multiple Docker registry instances, one per simulated CI system. Each registry is paired with a distinct KMS key.

- Cosign integration: Test images are signed in the setup phase using cosign with KMS-backed keys, and attestation metadata (build system annotations) is attached at signing time.

With the signing infrastructure in place, we validate the full matrix of policy enforcement:

Policy enforcement:

| Scenario | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|

| Image signed by correct CI with valid attestations | Admitted |

| Image signed by wrong key (key mismatch for registry) | Denied |

| Image signed with incorrect build system annotation | Denied |

| Unsigned image from trusted registry | Denied |

Observability:

| Scenario | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|

| BinauthZ metrics exposed at /metrics endpoint | Present |

Each test signs a container image with specific annotations, pushes it to a local registry, then attempts to deploy a pod referencing that image. The admission decision is captured from Kubernetes audit logs and validated against expectations.

go1 // 1. Sign image and add attestations 2 annotations := map[string]string{ 3 "build.system": "approved-ci", 4 } 5 intRef, err := crypto.SignImage(annotations, img, registryIP, hostPort, containerPort, kmsKeyURI) 6 if err != nil { 7 t.Fatalf("couldn't sign image: %v", err) 8 } 9 10 // 2. Deploy pod with signed image 11 po, err := pod.NewPod(ctx, *cfg, "signed-image-test", randomLength, 12 pod.WithNamespace(ns), 13 pod.WithContainerImage(intRef)) 14 if err != nil { 15 t.Fatalf("couldn't create test pod: %v", err) 16 } 17 18 // 3. Validate admission decision via audit logs 19 filter := func(annotations audit.AuditAnnotations) error { 20 if strings.Contains(annotations.Admission.Denied, "binauthz") || net.RequestDenied(annotations.Status.Code) { 21 return fmt.Errorf("pod %s was unexpectedly denied", po.Name) 22 } 23 return nil 24 } 25 26 err = audit.CheckPolicyDecisionsWithTimeout(ctx, po.Name, timeout, filter) 27 if err != nil { 28 t.Fatalf("policy validation failed: %v", err) 29 }

The E2E suite runs on every PR and provides confidence that changes to verification logic, caching, or error handling don't break the production path. It seems computationally expensive to run (infrastructure setup takes time), but the alternative of relying on actual cloud resources or discovering signature verification bugs in production are far more costly.

What’s Next for BinauthZ?

Alongside signing container images at build time, Block’s CI systems have also been adopting signed SBOMs (Software Bill of Materials) which is a cryptographically verifiable inventory of the components and dependencies that make up each image.

Next, we want to turn that inventory into an additional, enforceable guardrail that can surgically track and block specific risky packages via BinauthZ. We also want to explore leveraging this capability to help complete/target migrations to secure default patterns. We believe SBOM driven policies will help us meaningfully reduce risk at scale.